The size of cardiovascular studies is one factor forcing health systems and practices to consider the cloud for storage.

Growing need for storage space

As technology produces bigger and more detailed studies, hospitals and practices are running out of space to store their data. Some of the challenge is driven by cardiovascular studies, which are among the largest of medical files. Add the need for interoperability so that all health professionals can access studies quickly, and the cloud—the buzzword for somewhere out there on the internet that tends to inspire both love and hate—emerges as a likely solution.

Despite reservations that some professionals have about the cloud, its use is on the rise. In early 2018, BCC Research, of Wellesley, Mass., projected that the healthcare cloud computing market will reach $35 billion by 2022 with an annual compound growth rate of 11.6 percent, and the technology conference host Interop ITX named enterprise data storage the biggest factor driving changes in IT infrastructure. Meanwhile, Blain Newton, executive vice president at Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) Analytics, says cloud computing spending is growing four and half times faster than traditional IT expenditures. He predicts that rate will jump to six times—to as much as 60 percent of IT spending—over the next few years.

Security still a worry

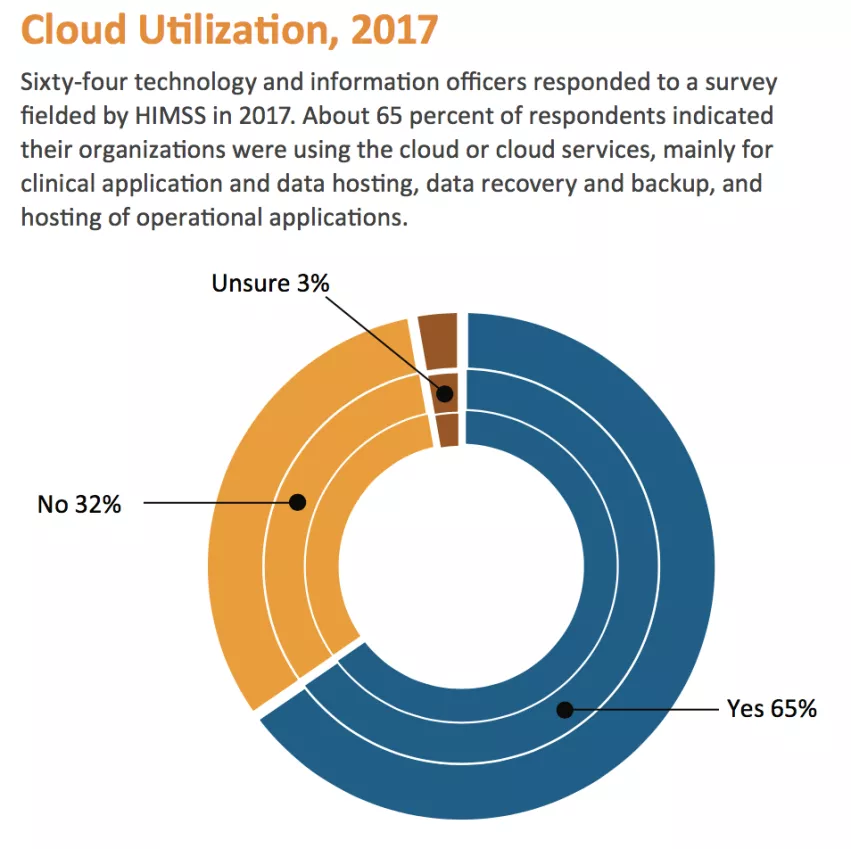

Regardless of spending trends and what industry leaders see as good business reasons to make the jump to the cloud, a 2017 HIMSS study found that a third of hospitals haven’t adopted cloud-based image storage. The survey responses suggested that some hospitals were resisting the lure of the cloud due to a fear of hackers.

Such worries are overblown, according to Val Kapitula, of Sacramento-based Paragon Consulting Partners. “A community hospital IT manager may have a lot of hesitancy and general fear of not having local control of imaging data—but that perception is changing,” he says. “I find that fear [of the cloud] is rapidly subsiding in large enterprise IT steering committees. But, depending on the size of the hospital or practice and the sophistication of the IT team, understanding of secure cloud options can be variable.”

As big-platform, security-expert players such as Amazon, Google and Microsoft enter the cloud-imaging storage field, Kapitula is seeing more hospitals adopting hybrid storage models that incorporate a mix of on-site and cloud-based storage.

Range of options

“Cardiology studies are very large and growing each year,” says Scott Nicol, who has been the cardiology informatics lead for the heart and vascular institute at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit since 2016. “We used to see echo studies in the sub gigabyte for an entire study, and now we’re seeing these at 7 or 8 gigabytes in some cases.”

Henry Ford began using limited cloud capacity in just “the last few months” to facilitate sharing of cardiac studies between regional hospitals and physicians in Ohio and southeast Michigan—although they have been sharing other imaging studies for “some time,” Nicol says. The cloud sharing replaced their old protocol of sending DVDs and other media that can be incompatible or proprietary. But, Nicol adds, internal storage is still more cost-effective for large systems due to the number of studies such systems perform and the file size of images. He thinks that cloud storage probably is more feasible at this point for cardiology practices than for large health systems, considering the complexities and expense of IT staffing, hardware and meeting HIPAA privacy standards.

For the average practice to make the move to the cloud, costs range between 20 and 40 cents annually per archived study, depending on the size of the file, Kapitula estimates. For that price, the practice would get storage and support. Another expense that practices should budget for is the usually one-time cost of migrating legacy imaging and respective data/reports to the cloud. For clean and properly normalized data, that typically runs about $4,000 per terabyte. Depending on the procedure type, a terabyte of data may equal 15,000 to 40,000 records.

Kapitula is seeing some practices commit to building an in-house support team for imaging storage, but “most cardiology practices want to be in the medicine business, not the IT business,” he says. “So, the trend [among practices] is to outsource.”

Matthew Hayes, CIIP MBA, information systems enterprise imaging architect at Ochsner Health System in Louisiana, who has worked in both the private practice and hospital sectors, notes that the dynamic characteristics of cardiac studies require that motion, quantified measurement and post-processing be accommodated in the cloud.

The trends Hayes is seeing are similar to those noted by Kapitula and Nicol. “Large systems are still settling for insourcing archiving” due to security and cost concerns, he explains, whereas he believes medium to small practices—“those who can’t afford a full time IT department”—are more likely to move to the cloud.

Ochsner is migrating to an in-house archiving solution, which Hayes says will replace some of the several older, outsourced storage platforms currently in place and take advantage of imaging’s machine learning capabilities to help improve clinical performance use and, ultimately, patient outcomes.

Source: HIMSS Analytics. (2017). 2017 Essentials Brief: Cloud. Accessed at: https://www.himssanalytics.org. Reprinted with permission.

Synergy with AI

Newton reports that among organizations that have made the switch to the cloud, 75 percent of the IT experts and clinicians surveyed think the cloud will have a positive impact on clinical care. This is possible, he notes, because of emerging artificial intelligence (AI) applications that interact with stored imaging files.

“You start to think about the leverage [of] cloud based-radiology and cardiology imagery review in a small rural hospital because of the access to cloud-based, AI-enhanced imaging,” he says, “and it’s game-changing.”